In Lean manufacturing, the goal is simple: eliminate waste and keep what adds value. Now in widespread use, the principles of Lean provide value across markets for a variety of very different companies. However, standard Lean thinking alone cannot address the specific pressures of manufacturing in a highly seasonal industry.

Waste almost always means the same thing, no matter what you are manufacturing. If an employee uses a tool a hundred times a day, there is waste if he or she has to walk to the other side of the factory to bring it back to his or her work station. To eliminate that waste, the tool should be located closer to where the work is being performed. If one employee is overworked and burning out and another is always looking for ways to fill his or her time, labor is being wasted. You can cut that waste by balancing workload across your workforce.

As Milford, New Hampshire’s Alene Candles grew from an entrepreneurial small business into the largest contract producer in the American candle market, it has retooled manufacturing processes to meet increasing production demands. Now, the company is applying concepts from Lean manufacturing to tighten up manufacturing to match customer needs, maximize profit, and maintain a reliable workforce.

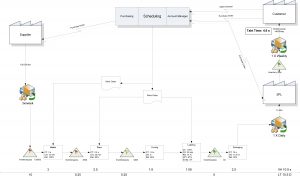

In the past two years alone, Alene has completely redesigned its overall manufacturing process. It was designed for big, high-volume orders, but many customers were buying small-batch boutique products. A review revealed that change-overs for these smaller orders were a major source of waste. “We looked at the way we were manufacturing and decided that our process start-to-end wasn’t supportive for that small customer,” says Alene Candles COO Jeffrey Armstrong. So, Alene started with a fresh sheet of paper, redrew the process, and initiated changes: the layout of the factory, the design of work centers, and the function of work centers. This allowed the company to balance labor more appropriately and increase output, while using less labor and alleviating stress on employees.

Some useful tools for making a manufacturing operation more Lean include value stream mapping, whereby a business charts out a process from start to finish to identify time and cost hang-ups; kaizen events, when a small group of employees eliminate waste in a process they know well by applying simple analysis tools; and employee trainings so everyone can see and eliminate waste in their corner of the business. Armstrong confirms Alene utilizes all of these strategies.

However, he warns not to get distracted by a theory, however useful, when running a business. Like any system, Lean manufacturing is designed to address particular issues, and like any idea it comes from a particular place and time. Armstrong, a former USAF Captain and three-decade veteran of manufacturing operations, says that earlier in his career, what has now become Lean manufacturing was termed “just-in-time” manufacturing. Developed in post-War Japan, a central aim was thrift, to acquire inventory “just in time” and not too early. However, the business environment for an early Toyota is different than the one Alene Candles inhabits generations later. While unemployment was high in Japan at the time, Alene competes for labor in New Hampshire where the unemployment rate sits around three percent and Ohio where the labor market is similar. Additionally, while car production can continue year-round, the candle market is highly seasonal. Alene produces the vast majority of its candles in a six-month window with production whirring hottest in September and October. So, Alene has bent Lean manufacturing to meet its specific demands and opportunities.

To Armstrong, the most important element of success in seasonal manufacturing is appropriate staffing. “You’re only going to be successful if you have the staff that you need and they’re properly trained and they know how to do what you need them to do,” he emphasizes. A simple application, or misapplication, of Lean manufacturing might suggest drastically slicing both number of workers and overall payroll in off months. Certainly, the argument could be made that keeping highly-qualified workers in the factory when there is less work demanding less skill is a clear example of waste. However, leaders must see the entire model as a cohesive package. While cutting staff to a bare minimum might scrape extra profit out of January and February, responsible business practice considers a longer time horizon.

At Alene, staff can triple or quadruple between low- and high-production months. Lean manufacturing offers a lot of benefits in such periods of transition. Most importantly, Lean manufacturing can create the kind of good design that makes a seasonal employee’s job as straightforward and learnable as possible, which in turn makes that employee more effective more quickly. Additionally, in a competitive labor market for employers, Lean manufacturing cuts down on employee dissatisfaction. Ideally, it makes a worker’s job more efficient so they do not identify an easier way while following a convoluted work design, it shows them why their work is important to the project by leaving only the parts of their job that matter to the process, and it saves them from resenting slackers (or being one) by distributing the workload in a way that makes sense. Armstrong reports, “We have a lot of seasonal employees that want the seasonal work and they look forward to it every year.”

Still, the underlying challenge persists. How does an organization scale up fast with unfamiliar workers in regions where other jobs are available, and without sacrificing quality? The solution requires a flexible reworking of Lean thinking.

A flexible workforce is critical in the off season, Armstrong says. When operations might slow to a trickle, it is best to keep workers adept at a number of functions as not all specialties may be required at once. When the orders flood in, though, the most important asset to effective production is highly skilled, reliable labor with expertise that can be shared with seasonal workers to make them more effective in a sprint.

The best way to resolve these multiple requirements is not the “Leanest” way. “There’s a core staff that you have to have, they have to be the best employees you can find, and they have to be the most versatile trained employees,” advises Armstrong. At Alene, the core cohort of knowledgeable, trusted employees that brings newcomers up to speed in the busy times doubles as the cohort of flexible workers who manage all functions in the slow times. “You will actually find yourself probably carrying extra staff in the slow season, and certainly an extra wage rate, and that is part of the investment for being successful in the busy season.” This strategy includes overpaying; on its face, there is waste. When it is slow and a machine operator is driving a lift truck or a line lead is boxing candles and a business compensates them at the rates owed a machine operator and a line lead, on that day the compensation scheme includes waste. Their skills are not “just in time.” However, the investment pays off in the busy times when the core workers represent the foundation of a workforce. What looks like waste is not waste at all.

In fact, Alene continues to invest more in this particular type of ‘waste.’ Armstrong confirms efforts are in the work to strengthen the tutorial infrastructure on the factory floor to best utilize Alene’s human resources. Additionally, Alene embraces other good waste through its Conscious Leadership program, which gives employees time to play at work, space to breathe, and opportunities to treat their feelings authentically. All of these allowances might take a worker away from his work station, but Armstrong says it fosters a more collaborative community that drives down turnover and burnout.

In fact, Alene continues to invest more in this particular type of ‘waste.’ Armstrong confirms efforts are in the work to strengthen the tutorial infrastructure on the factory floor to best utilize Alene’s human resources. Additionally, Alene embraces other good waste through its Conscious Leadership program, which gives employees time to play at work, space to breathe, and opportunities to treat their feelings authentically. All of these allowances might take a worker away from his work station, but Armstrong says it fosters a more collaborative community that drives down turnover and burnout.

Alene’s answer to the challenges of seasonal production draws from Lean manufacturing, but adapts the concept to increase flexibility and ensure a sustainable, skilled workforce. Armstrong says anyone in operations should observe processes first and develop strategies from there: “Lean manufacturing, good engineering, all of it comes down to common sense.”

About Alene

Alene develops, designs and creates candles for some of the world’s most recognized retail, boutique and cosmetic brands. Their aptitude for innovation not only assures optimal candle quality, but delivers rapid turnaround for your project. Alene’s artisanship combined with efficiency makes them an effective solution for your business needs, no matter the size or complexity. Because they are solely a contract manufacturer of private label brands and do not produce their own line, they are able to focus entirely on manufacturing your candle to your exact specifications.